Research

Mixed layer depth and mode water detection

Mode water is firstly introduced to describe the phenomenon of 18 Degree Water in the North Atlantic that repeatedly appears as a thick near-surface isothermal layer in winter. Extended to define water masses with nearly uniform properties over large volumes, mode waters are subsequently recognized and described in every ocean basin, mainly situated on the equatorward side of major mid-latitude ocean fronts. Commonly formed due to wintertime convection, these homogeneous water masses can be thought of as an intermediate state of fluid above the permanent thermocline that carry a memory of previous atmospheric forcing and a potential of reshaping the interior ocean stratification via subduction.

Thinking of the homogeneity of both surface mixed layer depths and mode waters in the interior, we have developed an algorithm to detect their presence from several profiling platforms. A brief intro can be found in our paper of the South Atlantic Subtropical Mode Water. By co-locating these mode waters with satellite-deduced mesoscale eddy positions, it further allows for an evaluation of the role that eddies undertake in water mass ventilation and the associated heat content uptake.

The video above depicts one trajectory of Agulhas Ring identified from satellite altimetry maps. The diamond markers locate the nearby Argo profiles that are associated with each eddy contour (blue for those at the center while green for those at the periphery). Before all else, we notice that such anticyclonic eddy can travel from the Indian Ocean to the South Brazil Current with more than 3 years to cross the entire South Atlantic. Mode waters thicker than 100 m are found along the trajectory from January to October 2015 (not shown here), which provides a proof of water mass subduction at the mesoscale.

Nonlinear Ekman theory

Classic Ekman theory applied to the ocean surface layer predicts a transport perpendicular to the wind stress and inversely proportional to the Coriolis frequency, f. A modification to this has that the transport is instead inversely proportional to the absolute vertical vorticity, f+ζ (Stern, 1965). This modification has recently been extended to more complex curvilinear currents by Wenegrat and Thomas (2017).

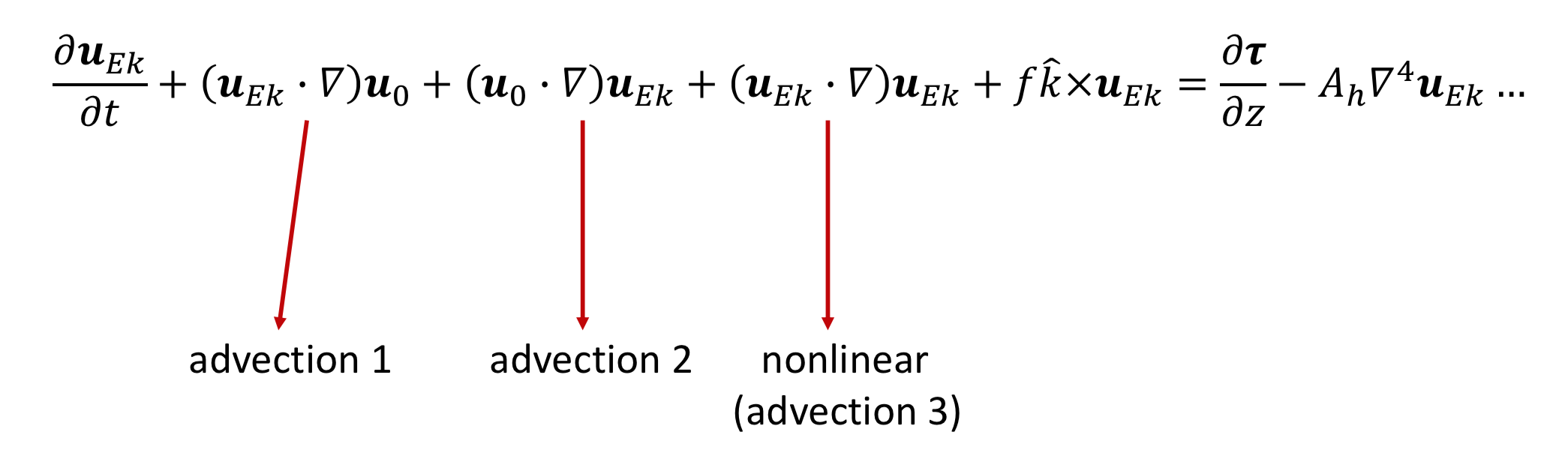

Following these studies, we first consider a zonally uniform wind stress acting on an axisymmetric balanced eddy (either cyclonic or anticyclonic). The equation below describes several advection terms in consideration, where u0 indicates the background velocity of the given vortex. Since a time-dependent term is retained in this Ekman equation, the need of shifting from Cartesian coordinate to a curvilinear coordinate is eliminated.

The video below shows Ekman pumping (or divergence of horizontal transport) for three cases:

a) upper panels that only consider advection 1;

b) middle panels that take into account both advections 1 and 2;

c) lower panels for a fully nonlinear result.

Accounting for a balanced curvilinear flow leads to counter-intuitive conclusions, e.g., that the Ekman transport need not to be everywhere perpendicular to the applied stress. In addition, our model allows for transients, as shown in the video. By adding the “real” nonlinear advection term (bottom panels), the signals of pumping are pushed southward.

A more complex system, i.e., this slab Ekman layer coupled with a two-layer shallow water model can be found in our paper: Interaction of Nonlinear Ekman Pumping, Near-Inertial Oscillations, and Geostrophic Turbulence in an Idealized Coupled Model